HINDSIGHT IS 20/20

I had an idea of what a dad should be. This idea was shaped almost entirely from popular media. I imagined a man who golfed. Who barbecued. A man who liked hockey.

I did not have such a dad. My dad read. And liked math. He curled.

I was very young when I bought him a comedy tape; Bill Cosby, if I recall. I figured that somehow, by listening to it, he’d be transformed into Dr. Huxtable. He’d become an affable, Canadian Tire dad. An ‘aw shucks’ dad who’d take me fishing.

When I found that he hadn’t listened to the tape – that he had no intention of listening to the tape – I felt defeated. He told me that he didn’t have time for such things.

I shift in my seat as I write this.

It was another string of barbed wire on the vast

prairie of misunderstanding between us.

He died a few years back now. Alzheimer’s. Slow and tortuous it was, but the grinding process turned his more wounding shards to beach glass. Gentler, less familiar aspects of his personality were revealed by the disarray. He died precipitously one Sunday.

Fool that I was, I wasn’t expecting it.

With each year that passes now I see him framed in a rear view mirror, the shadowy text reading: Objects in mirror are closer than they appear. And the further I pull away the clearer they become. Slowly, my blood chills with my utter lack of comprehension.

Fool that I was.

About the tape: He didn’t have time. Of course he didn’t. He had four kids. He was a young accountant with his own practice and then a junior partner in a growing firm. He had responsibilities that, even now, I cannot fathom. From an early age, he contributed to his family and supported his mother.

He died precipitously one Sunday.

Fool that I was, I wasn’t expecting it.

He had grown up a fatherless boy. A poor boy. A hard-working boy who not only put himself through university by working in the mines, but also found a way to underwrite an equally disadvantaged friend’s university education.

He made an odd match, marrying my mother. Alike in their damage and aspiration; unalike in their damage and aspiration. Mother Nature enjoys a good laugh.

Babies came. Spaced like commuter trains they were, each precisely 18 months apart. One, two, three, four, and the fifth that was unexpectedly – and mercifully – derailed.

Who could imagine such a thing today? Four, almost five, preschool children at home at one time? Floors to wax and a perennial pyramid of cotton diapers to wash and dry.

I came of age in a time of perfect contraception and shining appliance’d convenience. His was not such a time.

He liked flowers. He favoured the most pedestrian: the flower known officially as dianthus, but commonly as ‘pinks’. He loved the way they smelled. Only now, as an adult, do I recognize what it was that he loved – the pungent pepper of this garden soldier is intoxicating. I scoffed at the idea that a man who loved columns and ledgers could love anything so ephemeral. It wasn’t allowed. Today, I grow four types of pinks in my garden.

Ask me about his father, my paternal grandfather. I can tell you almost nothing about my paternal grandfather. No one ever spoke of him. Legend has it that my grandmother packed up the kids, abandoning him on the prairies, and moved to Vancouver. I don’t know exactly why.

If life was hard before, it wasn’t much easier after. His mother worked as a nurse. His room was let out to a lodger and my dad slept in the kitchen. He had a morning newspaper route, and he was, by all accounts, a very good boy. Dutiful. Earnest.

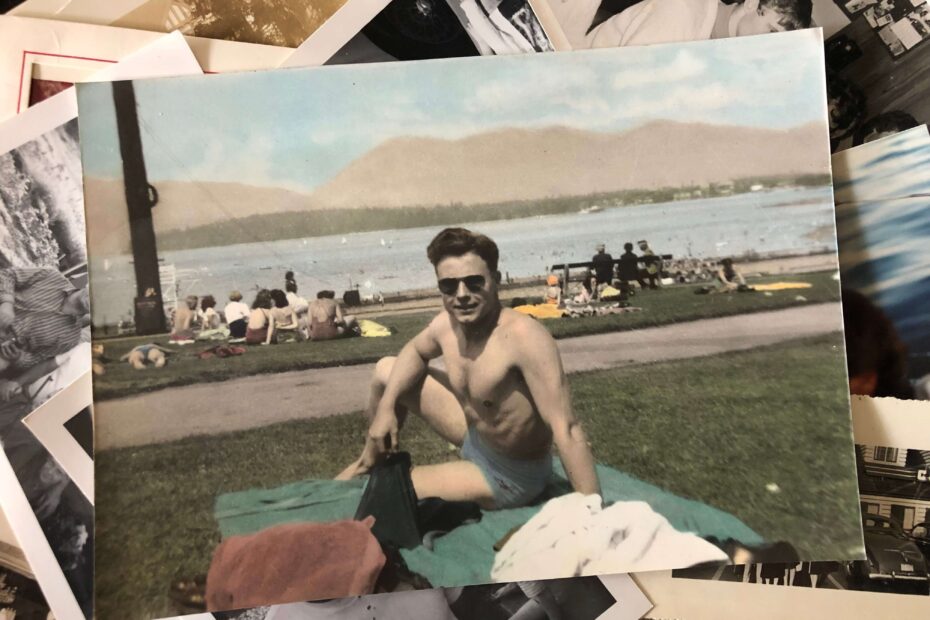

In photos I see a beautiful young man with an astonishing head of wavy, dark brown hair. In one photo he wears swim trunks and he smiles straight at the camera. In another he horses around with a friend and a tennis racket. He horses around?! I have never been able to reconcile this levity with my dad.

The smiles belie what will have been a tense existence. Being a boy of scant means as well as an absent father – a father absent without the wartime dispensation of untimely death in conflict – will have placed him in the crosshairs of incivility. I never stopped to consider any of this until, well, until it was too late.

My father had two boys and two girls. Not on purpose; he just had them. He had no idea what to make of us. Having lacked the daily example of a father, he defaulted to rules and discipline. His methods and ideals were firmly set in an earlier time. To him, everything about the 60s and the 70s was an effrontery. Of course, we hated him for this.

Hate has a long spine. The jaws of hate swing round to bite you on your very own backside. I understand now about fatherlessness. I understand the burden of responsibility. Where I saw an unyielding authoritarian, I now see a resolute man walking a high wire. A high wire with not only no safety net, but with a landscape of jagged rocks beneath. I see the weight of small squirming bodies perched on his shoulders, a bride, the monthly maintenance of a mother, the doubling up of that responsibility for the bride’s mother, as well as the hand-over-hand, slow building of a career. Borne daily, weekly, yearly; all the while inching ahead.

And he did.

My dad provided well for us: private schools, country clubs, skiing lessons, and tropical holidays. He inched ahead. The landscape beneath his children was as unfamiliar to him as his was to us. I don’t think he ever lost sight of those rocks below him.

The landscape beneath his children was as unfamiliar to him

as his was to us.

In the same way he taught himself, he tried to teach us how to navigate, how to construct safety. I put little stock in this. I wished for a Hallmark dad, a television dad who convened touch football games and thought nothing of letting the kids have a beer.

I never saw his struggle.

I never understood his fears.

I never appreciated his enormous and hard-won success.

I do now.

Fool that I was.

What I wouldn’t give to be able to say,

Happy Father’s Day, Dad.